APRIL 2025

TUESDAY, APRIL 1

Trois Crayons celebrates the art of drawing from the 15th to the 21st century. From in-person exhibitions and collaborative events to our monthly newsletter and social media activity, we connect the global drawings community.

Coming Up

Greetings from Trois Crayons HQ.

Following a busy month for the Old Master drawings market which included the major art fairs of TEFAF in Maastricht and the Salon du Dessin in Paris, bolstered by the wider Semaine du Dessin, this month’s newsletter takes a decidedly more modern turn. After the news and events sections, Henri Michaux, the Courtauld Gallery, and the experimental mescaline drawings of the 1950s take centre stage, with insights from Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen, Ketty Gottardo, and Linda Karshan. The customary selection of literary, visual, and audio highlights is followed, as ever, by the ‘Real or Fake’ section.

We would also like to thank all who attended our board game afternoon in Paris and battled it out over madeleines and copies of Attribution!. Charmant. We are grateful to Christie’s and the Old Master drawings department for their generous hospitality.

For next month’s edition, please direct any recommendations, news stories, feedback or event listings to tom@troiscrayons.art.

NEWS

In Art World News

In New York, The Frick Collection is due to reopen its doors on April 17 following a five-year closure. The new Cabinet gallery will host an exhibition of ‘Highlights of Drawings from The Frick Collection’. In New Haven, The Yale Center for British Art has also reopened following a two-year closure. The Drawing Foundation has published on their website the recordings of the various panel discussions, and lectures held in New York during Drawings Week 2025. Our own event, in partnership with The Drawing Foundation and in association with Master Drawings New York 2025, can be viewed here. This Sunday, April 6, The Drawing Foundation is also hosting The Drawing Competition 2025 at the National Arts Club in New York, a full day of drawing from multiple live models.

In Paris, a rare work by Francesco Primaticcio led the March drawings sale at Christie’s as it soared to a record price of €660,000. In the latest volume of the recently relaunched The British Art Journal there is a fascinating article by Meredith M Hale which identifies the 1951 thief of a Van Dyck oil sketch from Boughton House as L.G.G. Ramsey, erstwhile editor of The Connoisseur. After more than 70 years of absence, the sketch has now returned to Boughton.

In Exhibition and Art Fair News

In Paris, although the Semaine du Dessin may be officially over, several gallery exhibitions remain on view for a few more days at least. Among those: the exhibition at Nicolas Schwed closes today, April 1; The exhibition at the Pierre Brost Galerie continues until tomorrow, April 2; the exhibition of Mathieu Néouze at Galerie Ambroise Duchemin continues until April 5; the exhibition at Galerie Nathalie Motte Masselink continues until May 10; and the exhibition at Galerie Alexis Bordes continues until May 16. In London, Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert is hosting an exhibition of drawings by Celia Paul which continues until May 2.

Federico Zuccari ‘Artista Universale’ runs from 9-12 April with lectures at the Accademia di Belle Arti from 11-12 April.

In Lecture and Event News

In York, For Art History hosts its Annual Conference from April 9-11. In Chicago, on April 10 at 18:00, Jamie Gabbarelli will give a lecture at the Art Institute of Chicago, ‘Working on Paper - The Shared History of Drawing and Printmaking’. The event is free but registration is required. In Rome, a conference on Federico Zuccari, Federico Zuccari ‘Artista Universale’, organised by the new journal L’IDEA, will be held at the Accademia di Belle Arti from April 11-12. The programme features an impressive line-up of speakers and will also be livestreamed (April 11, April 12). A recording of a recent webinar on the legendary art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, featuring his great-great granddaughter Flavie Durand-Ruel, has been posted on Youtube by the Wildenstein Plattner Institute.

In Literary and Academic News

Master Drawings has published the Spring edition of the journal, focusing on ‘Draftsmen in Rome’. In conjunction with the exhibition of drawings from the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi Erizzo in Verona opening on April 5, a 360-page catalogue authored by Thomas dalla Costa, Giovanna Residori, Maria Aresin and Gabriele Matino is also due to be published this month. The four-year research project was funded by the Getty Paper Project. A new three-volume catalogue on the life and works of Joseph Vernet, Car c'est moy que je peins, by Emilie Beck Saiello is also due for publication this month. A new online catalogue raisonné of Samuel van Hoogstraten, a collaboration between the RKD and the Museum Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam, is due to be published this month as an RKD Study. A conference hosted by the RKD in The Hague will celebrate the publication on April 17. Regular tickets are €15e, students €7.50 and online participation is free. A call for papers on Mannerist drawings has been issued by the museums of the city of Aschaffenburg and the art history institutes of the universities of Bonn and Mainz. Proposals for the conference, FOCUS 1600. III Aschaffenburg Symposium on the architecture and fine arts of Mannerism: Unlimited possibilities? Drawing in Mannerism (Aschaffenburg, September 11-13, 2025), are due by May 11.

In Acquisition News

No doubt there will be news in the coming weeks with results from the fairs in Maastricht and Paris. For now, here are several recent museum acquisitions which have already been announced. A pastel portrait of Louis XV as a child by Rosalba Carriera, which was acquired by the Palace of Versailles in 2024, has recently gone on display. A pastel by Gad Frederik Clement has been acquired by the Musée Pont-Aven, as reported by La Tribune de l’Art. The museum has also acquired a drawing by Jan Verkade from Agnews Brussels, again reported by La Tribune de l’Art. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco has acquired a drawing by Domenico Gnoli from Stephen Ongpin Fine Art. A remarkable watercolour by Edmund Blampied has been acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago from Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker Ltd.

EVENTS

Claude Lorrain, Landscape with the Voyage of Jacob, 1677, oil on canvas, 991 mm x 1241 mm x 130 mm (framed), Clark Art Institute, 1955.42.

This month we have picked out a selection of new and previously unhighlighted events from the UK and from further afield. For a more complete overview of ongoing exhibitions and talks, please visit our Calendar page.

UK

Wordlwide

Demystifying drawings

Henri Michaux at the Courtauld Gallery: Mescaline Drawings, Artistic Process and the Karshan Gift

Henri Michaux: The Mescaline Drawings, a foreword to the catalogue by Dr Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen, Head of the Courtauld Gallery

“The magnificent gift of modern drawings presented to the Courtauld Gallery in 2020 by Linda Karshan in memory of her husband, Howard, not only brilliantly extends The Courtauld's renowned drawings collection, but is also transforming our programme of exhibitions and displays, especially in the Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Drawings Gallery. The Karshan Gift includes two exceptionally fine works by the Franco-Belgian poet and artist Henri Michaux, which are eloquently representative of Linda and Howard's taste and interests. Not only are the drawings the first by Michaux to enter The Courtauld's collection, but they represent a type of drawing which was hitherto almost entirely absent. The process of drawing has surely always been a means to investigate, study and learn, but this analytical and creative principle is given a completely new dimension in Michaux's utterly remarkable personal language of calligraphic marks and gestures. With its topography of dense seismographic lines, one of the Karshan drawings is revealed to have belonged to the group of works that Michaux made as part of his exploration of the effects of the psychedelic drug mescaline. It was the striking quality of this work - somehow both frenetic and lyrical, compressed and expansive - that inspired the present exhibition.”

Henri Michaux (1889-1984), Untitled, 1962, Graphite, brown and black inks on paper Monogram HM lower right, 401 x 270 mm. Private collection © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025

Henri Michaux (1889-1984), Untitled, 1956, Graphite, black and coloured inks on paper, 184 x 131 mm. Private collection © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025

On mescaline drawings and artistic process, a Q&A with Dr Ketty Gottardo, Martin Halusa Curator of Drawings at the Courtauld Gallery

Michaux was a Franco-Belgian poet, writer and visual artist, known for his experimentation and introspection across a range of media. For those unfamiliar with Michaux and his mescaline drawings, could you provide an overview of his artistic approach and explain what makes these exhibited works particularly significant within his broader body of work?

Henri Michaux (1899–1984) was first a poet and writer before becoming a visual artist; his fascination with the world of words is evident throughout his work, both in his texts and in his art. At the age of 26, Michaux attempted painting for the first time and created his first ‘sign’ drawings, Alphabet and Narration, compositions of ambiguous pictorial signs resembling writing, to which he would return later in his career. During those early years, he painted and drew very little. His first exhibition of paintings and drawings did not take place until 1937 in Paris.

In the 1920s and 1930s, he met André Breton, the photographer Claude Cahun, Salvador Dalí, and André Masson, and encountered the work of Max Ernst and Paul Klee. However, it was his extended travels to South America and Asia between 1928 and 1932 that would fundamentally transform his art. His experiences with distant cultures and philosophies profoundly influenced him. He began practicing meditation, explored Taoism, and experimented with drugs as they were used by local populations in their rituals.

After reading Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception (1954), in which the author described his experiences with the psychedelic drug mescaline, a non-addictive substance derived from the Mexican peyote cactus, Michaux tried mescaline for the first time in early January 1955. This marked the beginning of a journey that lasted several years, during which Michaux sought to depict the inner workings of the mind through his art. These experiences transformed his artistic life, leading to an outpouring of distinctive drawings and writings.

Michaux’s controlled experiments with mescaline have become the subject of great fascination, and his resulting drawings are often described as surreal, frenetic, and transformative. Could you elaborate on his creative process under (and after) the influence of mescaline and discuss how these altered states shaped both his techniques and the thematic content of his drawings?

First, it is important to clarify that Michaux repeatedly emphasized how difficult, indeed, almost impossible, it was to create anything while under the effects of mescaline. His drawings came afterward. In the foreword to his seminal book Miserable Miracle, Michaux underscores a fundamental aspect of his so-called mescaline drawings: they were not created while under the influence of the drug, but in the hours or even days after its effects had subsided, emerging from what he described as the “vibratory motion that continues for days and days.” The drawings represent Michaux’s inner visions, based on his memory of those sensations and the notes he took following his experiments. Before the advent of brain imaging, attempting to use words and images to record the effects of psychotropic drugs on the brain meant capturing unverifiable mental images which were accessible only to the subject. For Michaux, drawing was always a process of discovery; the act and its outcome had to generate a kind of knowledge that he could not have conceived before making the drawing.

While the Courtauld exhibition presents a monographic display of 21 drawings by Michaux, one of which is Linda Karshan’s promised gift to The Courtauld, it also represents an important milestone in the study and exhibition of experimental art. Could you discuss Michaux’s place within the broader tradition of artists working ‘under the influence’ and explore how his work and this exhibition has deepened our understanding of altered states in artistic practice?

Michaux’s experiences with psychotropic drugs positioned him at the intersection of multiple domains, from science and medicine to spirituality and mysticism. He was neither the first nor the last artist to experiment with drugs. Antonin Artaud (1896–1948), Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885–1939), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), for example, preceded him, while Andy Warhol (1928–1987) used amphetamines—initially as a diet aid but later as a stimulant for artistic production. Yet, compared to these figures, Michaux appears more pragmatic in his approach. His experiences were carefully regulated; he took mescaline in a structured manner, often in solitude, with shutters closed, drinking only water (no coffee or alcohol), and listening to a curated selection of music, including classical (Olivier Messiaen, Gustav Mahler), contemporary, and traditional compositions (polyphonic music from the Aka tribe of Central Africa, Indian raga).

As Muriel Pic writes in the exhibition catalogue, the 1950s and ’60s saw a pharmacological revolution in Europe, particularly in Paris and Basel. The pharmaceutical industry had launched extensive research into psychotropic drugs, and it was within this context that Michaux, in collaboration with doctors, regularly experimented with them. He obtained mescaline through specialists such as Dr. Jean Delay of the Sainte-Anne psychiatric hospital in Paris, chemist Albert Hofmann of the Sandoz pharmaceutical laboratories in Basel, and botanist Roger Heim of the Natural History Museum in Paris. This collaboration also led to the production of Images du monde visionnaire (1963), a film produced by the Sandoz Laboratories, in which Michaux sought to convey through moving images the emotions and sensations that could not be fully captured in drawing or writing.

DRAWING OF THE MONTH

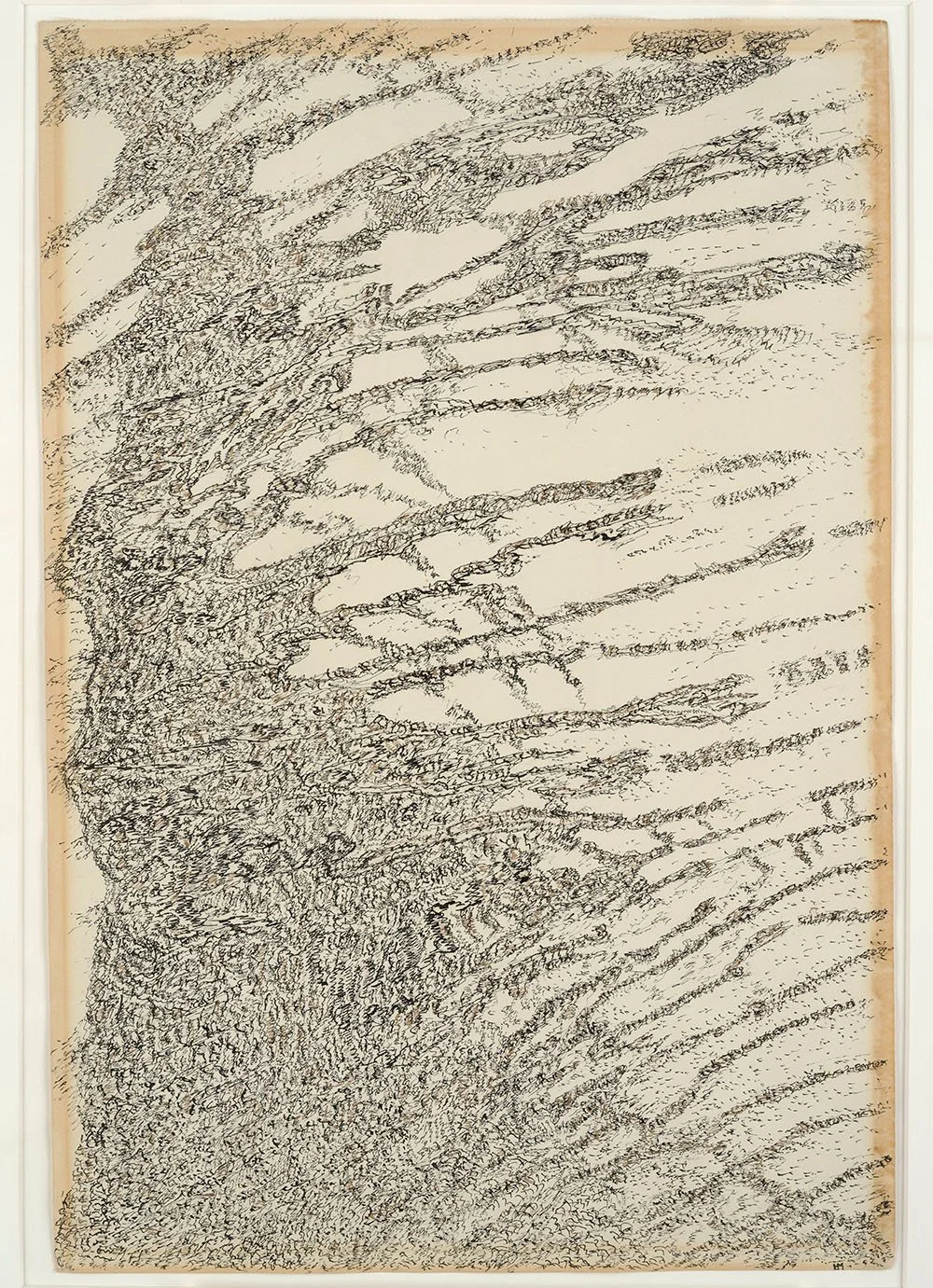

For our 19th drawing of the month, Linda Karshan, artist and President of ACLA, Athenaeum Comeliana de Litteris et Artibus, reflects on a highly personal drawing, a gift to the Courtauld Gallery in memory of her husband, Howard Karshan, and a highlight of the current exhibition, Henri Michaux: The Mescaline Drawings.

Untitled (Mescaline drawing), 1957

Pen and black ink on paper. Promised gift by Linda Karshan in memory of her husband, Howard Karshan. On long-term loan to The Courtauld Gallery, London

Following Ernst (and Ketty), I’ll focus my attention on the special nature of this drawing and its place in our collection at home. Considering the nature of the work, I'd like to quote Martin Kemp on Kenneth Clark's blindspot concerning Leonardo’s state of mind. Kemp refers to “the geometrical temper” of Leonardo's science and how it is intimately related to his feeling for the vitality of organic life. Reading more closely about Henri Michaux, I understood perhaps only yesterday that he considered himself a researcher, a scientist. He took mescaline to reach the vitality of organic life. His was a scientific frame of mind.

The drawings in this exhibition show nothing if not this vitality. Kemp goes on to talk about the organic complexity and living nature of Leonardo’s drawing, “right down to the minutest nuances of mobile form, [which is] founded upon the inexhaustibly rich interplay of geometrical motifs in the context of natural law”. This may seem to be a bit off-piste, but nevertheless, this is one of the important reasons that I am so taken with the drawings of Michaux, and why they hold together so well.

Michaux ends his wall text with these words: “Yet in spite of all the fissures nothing ever collapses”. I was taught to build a drawing so that it would not fall apart when you get up close. That was the Albers way. This drawing holds together, in spite of the fissures. That was always Howard’s and my criteria in selecting and buying a drawing.

The idea behind the Karshan Gift was to unlock the possibility of studying these drawings and exhibiting them beautifully, as we see here. It was meant to be a transformative gift, and it is. This season, we have not only this outstanding exhibition of Michaux’s mescaline drawings, but the display of the German and Austrian drawings, With Graphic Intent. It could be said that the Kandinsky in that exhibition is another ‘Drawing of the Month’.

The Michaux had a special place in our collection at home. For Howard and me, it was an old friend. It sat on a wall, just as you entered the flat, and Howard could see it from his bathroom as he shaved. That's quite important; Howard always kept within his sightlines those drawings that he particularly valued. In choosing the 25 drawings for the Gift, this work had pride of place, as did the Kandinsky. What makes it so unusual? Its beauty. We know it was made under the influence of mescaline, and Ketty will refer to that. But to my mind, the real beauty lies in its form. The figure is implicit, without being spelled out. And it's masterful in its execution.

As one walks into the Butler Drawings Gallery, the Karshan Michaux holds the wall like none other. It is the most spectacular drawing in an exhibition of excellent drawings. And it's the most complete. This is an important point. There's nothing one would change about it. It’s the drawing that captures the eye, and from which one begins to study the others. Concerning its placement, it's not there as a contrivance. No, it belongs there. It's the drawing you want there.

Concerning its acquisition, I'd like to add something for the youngsters who don't know the history of London galleries: the underbidder in the Christies auction was the late, great Nigel Greenwood, a dealer of distinction. Howard and I recognized this drawing in the catalogue and immediately decided to bid on it. Few in London, especially in those years, had an eye for Michaux. As Plotinus reminds us, “The mind sheds radiance on the objects of sense out of its own store.” We were among the happy few. It’s heartwarming to see how the public has received this gift.

Image © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024

This drawing is currently on display at The Courtauld Gallery in Henri Michaux: The Mescaline Drawings, until June 4, 2025.

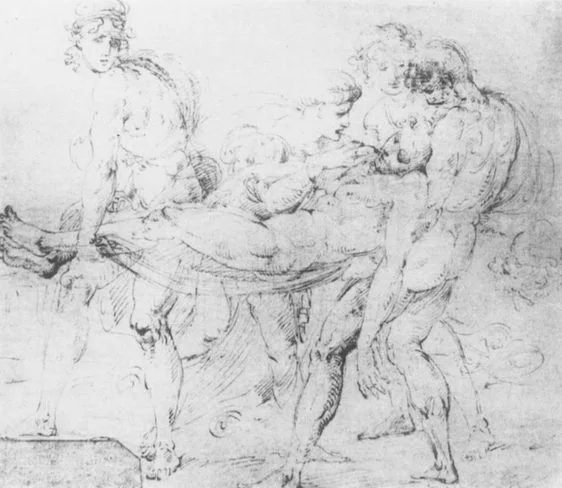

Real or Fake

Can we fool you? The term “fake” may be slightly sensationalist when it comes to old drawings. Copying originals and prints has formed a key part of an artist’s education since the Renaissance and with the passing of time the distinction between the two can be innocently mistaken.

For those with long memories, this forger has featured in these pages once before. Do you recognise their hand? Can you distinguish between their forgery and the original drawing? Extra marks for naming both the original artist and the forger.

Scroll to the end of the newsletter or click here for the answer.

Resources and Recommendations

to listen

The Story of Drawing: An Alternative History of Art - Susan Owens in Conversation with Claudia Tobin

In late September 2024, Susan Owens, former Curator of Paintings at the Victoria and Albert Museum, joined Dr Claudia Tobin, writer, curator, and art historian to discuss the topic of drawing and, in particular, Susan’s latest publication, The Story of Drawing: An Alternative History of Art. Ranging from Goya to Kusama by way of Michaux, Owens’s book serves as a starting point for the conversation which explores drawing’s role as an arena for experiment and candid expression.

TO watch

Amerigo Vespucci al Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe

Andrew Chen, professor at the University of Texas, introduces the illustrations of the “intermezzi” (theatrical performances designed to entertain guests during weddings) at the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe of the Uffizi in Florence. One of the prints features Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine navigator who would give his name to the Americas.

to read

Over the past four years, the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud in Cologne has re-examined its extensive collection of Netherlandish drawings. In this CODART feature, Annemarie Stefes, freelance researcher currently at the museum, reflects on a selection of new attributions, uncovered provenances, and new insights. The project will culminate in an exhibition, scheduled for November 2025, and a forthcoming publication, offering a fresh perspective on these artistic treasures.

answer

The original, of course, is the left-hand image.

Left-hand Image: Raphael, Death of Meleager, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Right-hand Image: The Calligraphic Forger, Death of Meleager, formerly in the Habich collection, Kassel

Although the true identity of this forger remains unknown, they have been dubbed the ‘Calligraphic Forger’ because of their recognisable tendency to copy Raphael’s compositions and to embellish his more sparse and functional use of lines. The artist was identified in 1913 by the German art historian, Oskar Fischel, through a group of homogeneously handled drawings in the style of Raphael and his pupil Timoteo Viti. Fischel gave the forger the notname of the 'Calligraphic Forger’ in a 1927 article in The Burlington Magazine, and speculated that the artist may be an Englishman working in the early 18th century, although more popular hypotheses argue that the artist is a 17th century Italian.

These two drawings depicting the Death of Meleager provide a particularly interesting case study. The forgery once duped the renowned connoisseur Giovanni Morelli, father of the ‘Morellian method’ of attribution. Morelli claimed that his friend Habich had purchased the 'original' at an auction in Germany. Fifty years later Fischel showed Habich’s drawing was, in fact, the product of a forgery.

For further reading, see Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, ‘Raphael's Heliodorus Vault and Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling: An Old Controversy and a New Drawing’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 132, No. 1044 (Mar., 1990), pp. 198-199; Oskar Fishchel: 'A Forger of Raphael Drawings', The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 51, No. 292 (Jul., 1927), pp. 26-31.